Forced “marriage” and sexual slavery in war lead to a variety of devastating but different outcomes for their victims. For this reason, many victims require reparations tailored to their specific needs and those of their children, according to an international group of researchers and activists meeting at York University next week.

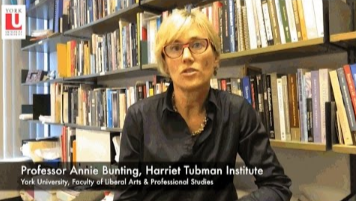

The Conjugal Slavery in War project, led by York University professor Annie Bunting, focuses on forced marriage in conflict situations in west and central African countries. Representatives of community-based organizations in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda and Nigeria, will come to York to discuss how interviews with more than 250 survivors of abduction for forced marriage are being used to advocate for justice and reparations.

The group will meet just weeks after the Canadian government announced Global Affairs Canada’s new Peace and Stabilization Operations Program to increase Canadian support for UN peace operations to tackle the causes and effects of these types of conflicts. Members of the team will speak about their findings at a public roundtable discussion Wednesday in downtown Toronto, co-sponsored by York, the Munk School for Global Affairs and Plan Canada. They will then travel to Ottawa to present their research to Global Affairs Canada.

Bunting, associate professor of Law & Society in York’s Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies and deputy director of The Harriet Tubman Institute for Research on Africa and its Diasporas, has been studying sexual violence in conflict situations since encountering silence about rape during the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Her current project on conjugal slavery in war, funded by the government of Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), began when the Special Court for Sierra Leone ruled that what happened to women in that conflict – forced marriage − was a crime against humanity.

Researchers are examining why the concept of marriage is mobilized in wartime.

“The difference between abduction and sexual violence in war, and assigning the status of wife to someone in conflict situations, is that the latter tends to be a longterm relationship,” says Bunting. “So some women stayed with the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda for almost 11 years. Sexual violence and gender violence are part of that relationship, but it doesn’t capture the whole of the harm.”

Graduate students from York, UBC, Birmingham and Witwatersrand are doing historical research in archives in the UK, Belgium and Sierra Leone, collecting primary data on marriage and slavery over time.

Bunting said that two years into a five-year project, researchers are surprised by some of the complexities of the victim-perpetrator relationship.

“While we know a lot about women’s experiences, we really know very little about men’s experiences of being forced into marriage or of being forced to take a wife, or being forced to be sexually violent,” Bunting said.

It has also become clear that children born of war may have different needs than their mothers in terms of their identity, ongoing stigmatization by family and community, education and psycho-social support, she said.

WHAT: Meeting of the Conjugal Slavery in War project, York University

WHEN: Nov. 14 to 16, 2016

WHERE: Monday, Nov. 14 and Tuesday, Nov. 15, 9am to 5pm, York University, Keele campus

(Interviews upon request on Monday and Tuesday)

Public roundtable: Wednesday, Nov. 16, 3 to 5pm, Munk School of Global Affairs, 315 Bloor St. West, Toronto, event details.